Spatial computing aims to be the next step in how we use computers. Instead of staring at flat screens, people and machines can interact with three-dimensional data that’s blended seamlessly into the physical world. Think of it as a layer that senses real-world geometry, understands where you are, and places digital information or objects in just the right spot. This umbrella term covers augmented and virtual reality, digital twins, advanced mapping, and the sensors and software that tie them together. For investors, the bet is on a broad shift in how humans and machines interact, not on a single killer app. Architects can “walk” a skyscraper before pouring concrete; surgeons can rehearse on a holographic heart. Every industry that manipulates physical things—buildings, engines, supply chains—will stand to benefit from spatial computing technology.

In this report, we highlight the top spatial computing stocks to watch, curated for pure-play exposure to the rise of AR/VR, digital twins, and immersive 3D tech.

Why spatial computing, why now?

After decades of prototypes, the pieces are finally clicking. Apple’s Vision Pro, launched in early 2024, proved a sleek, standalone headset can run full productivity software. It’s already sparked enterprise pilots from airlines to automakers. At the same time, generative-AI tools can conjure detailed 3-D assets from a sketch, while cloud GPUs stream those scenes to lightweight glasses, solving the “fat headset” problem. Meanwhile, 5G and edge computing have shaved latency to the milliseconds these immersive apps demand. Consumer pull is building too, as spatial apps promise immersive entertainment and more intuitive computing. Analysts now see the spatial computing market swelling from roughly $175 billion in 2025 to more than $1.7 trillion by 2037, compounding at ~21% a year.

For investors, that spells the early stages of a long adoption curve. Just as the PC, the web, and then mobile reshaped daily life, spatial computing promises a new default interface: computers that share our physical context. Value tends to accrue first to infrastructure providers—the toolmakers, component suppliers, and industrial platforms—before the market consolidates. These range from creation software to living digital twins that update in real time. If spatial computing becomes how we design, train, and collaborate, demand for these enablers could compound for years.

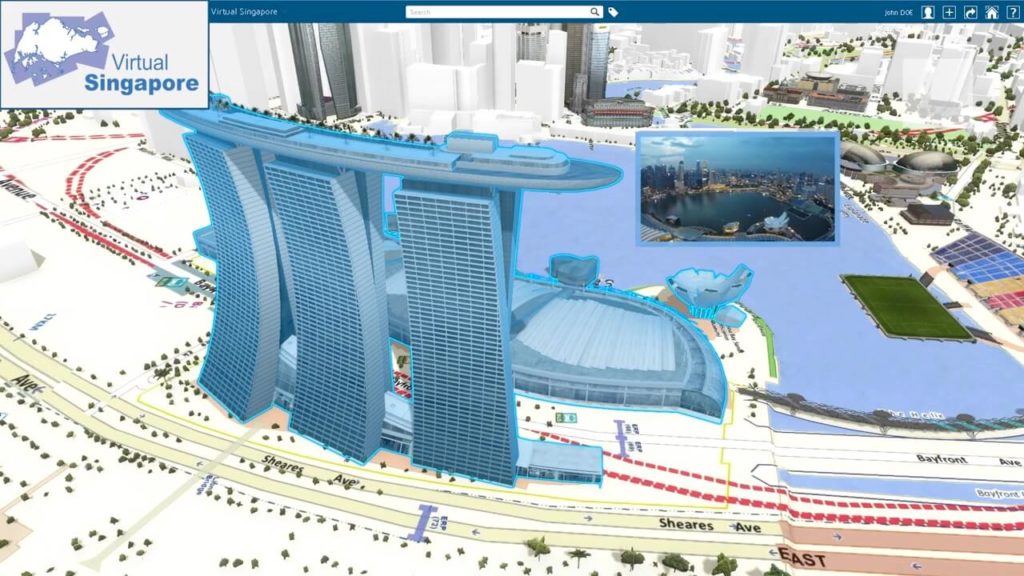

Spatial Software & Digital Twins

Spatial software & digital twins turn raw sensor feeds into living 3-D models. Digital twins, in particular, act as live mirrors of real-world systems, constantly updated with fresh data—highly useful for managing physical assets. This segment is sprinting from one-off architectural demos to always-on replicas of entire cities and supply chains. For investors, these spatial computing stocks offer subscription-style revenue, high switching costs, and data flywheels that feed downstream devices.

Unity Software (NYSE: U)

HQ: USA; Leading 3D engine for games, AR/VR, and real-time digital twins.

Unity Software is the go-to toolkit for building interactive 3D experiences, from mobile games to cutting-edge augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) applications. The company provides a real-time 3D engine that developers use to create content once and deploy it across many devices, including phones, game consoles, and now the latest AR headsets. Unity’s strategic position as a platform means it benefits as more industries explore spatial computing (the blending of digital content with the physical world). For example, Unity’s tools are already empowering developers to craft apps for Apple’s new Vision Pro headset, underscoring its central role in this emerging AR market.

Beyond gaming, Unity has made inroads into fields like automotive design and healthcare simulation – basically anywhere there’s a need for immersive visualization. This broad adoption serves as a “picks and shovels” play for the spatial computing trend: if companies want to build interactive 3D or AR experiences, they often rely on Unity rather than starting from scratch. As the long-term promise of the “metaverse” and spatial computing unfolds, Unity’s cross-platform versatility and massive developer community give it a strong foundation. The company is continually investing in tools (including AI features) to maintain leadership in real-time 3D content creation. As digital twins and AR/VR proliferate, Unity stands to be a key enabler.

Bentley Systems (NASDAQ: BSY)

HQ: USA; Digital twin leader for infrastructure and civil engineering.

Bentley Systems sits at the heart of spatial computing for global infrastructure, specializing in digital twin technology. Its iTwin Platform turns roads, railways, and water networks into living 3-D models that update as the real world changes, giving engineers a “single source of truth” they can stream to tablets, web browsers, or AR headsets. The company already serves clients in 194 countries and generates well over $1 billion in annual revenue, which funds steady R&D and a string of tuck-in acquisitions that broaden its reach. As spatial computing becomes the default language of infrastructure, Bentley’s platform approach—and its decades-long domain expertise—make it a compelling, durable compounder.

Strategically, Bentley is embedding itself wherever the physical and digital worlds meet. A deep integration with NVIDIA Omniverse lets teams render photorealistic twins in real time and walk through them in VR, no specialist game engine skills required. When users want to move from “pretty pictures” to actionable design, Bentley’s new generative-AI Copilot (debuted in OpenSite+) automates parking-lot layouts or earth-work optimization in minutes instead of weeks. Meanwhile, a partnership with Google injects photorealistic 3-D geospatial data straight into iTwin, making every model context-aware right out of the box. These moves push Bentley further up the value stack and create switching costs for customers who want their data and tools to flow freely.

Autodesk (NASDAQ: ADSK)

HQ: USA; CAD and design software giant expanding into cloud-based digital twins.

Autodesk is a backbone of 3D design across industries. Its software (like AutoCAD, Revit, and Maya) is used to create everything from skyscraper blueprints to Hollywood animations. Whether you’re building an augmented reality walkthrough of a new building or a virtual reality training simulation for a factory, chances are the underlying 3D models and blueprints were crafted with Autodesk’s tools. The company has steadily evolved its offerings to stay at the forefront of 3D technology. For example, Autodesk introduced a cloud-based digital twin platform (“Tandem”) to help architecture and engineering firms turn designs into living digital models of buildings. It has even partnered with NVIDIA to enable immersive design reviews, running Autodesk’s high-end visualization software via cloud streaming to VR headsets.

Autodesk represents a mature, picks-and-shovels spatial computing stock. As more enterprises adopt AR/VR for design, training, and collaboration, Autodesk stands to benefit indirectly from increased demand for detailed 3D content. The company’s tools are deeply entrenched in workflows for construction, manufacturing, and media, giving it a strong moat. Put simply, many spatial computing experiences will require precise digital models of the physical world. Autodesk’s decades-long dominance in creating those models means it could remain indispensable. Additionally, Autodesk’s move toward subscription cloud services and integration of emerging tech (like AI-driven generative design) provides it with steady cash flow and the ability to invest in new spatial computing use cases.

Display & Haptic Interfaces

Display & haptic interfaces are the senses of spatial computing: microscopic screens, waveguides, and vibration engines that fool your eyes and fingertips into believing digital illusions. After decades in the lab, costs are falling and image quality has hit “retina” territory, igniting a scramble among headset makers. This segment of spatial computing stocks includes component suppliers whose patents and manufacturing know-how operate like tollbooths on every future AR or VR device.

Vuzix (NASDAQ: VUZI)

HQ: USA; AR smart glasses maker with a focus on enterprise and optics.

Vuzix builds augmented reality eyewear: smart glasses that can display digital information in your field of view. The company has carved a niche in enterprise and industrial markets, offering lightweight glasses that engineers, warehouse workers, or surgeons can wear on the job. Vuzix has been in this space since the 1990s and holds a broad patent portfolio (over 425 patents in optics and display tech). Its hardware includes both the smart glasses themselves and key components (like waveguides, the transparent display elements) that enable heads-up information delivery. In short, Vuzix provides the “last mile” interface of spatial computing: the actual glasses that put digital content into a user’s line of sight.

Real-world deployments underscore the potential. For example, Amazon has equipped some warehouse maintenance teams with Vuzix smart glasses to enable a “see-what-I-see” remote expert assist: a technician on-site can share their view via the glasses, while an expert guides them through complex fixes. This kind of use case improves productivity and safety, highlighting the practical value of AR in industry. Vuzix’s long tenure and focus give it credibility in a field where tech giants are also circling. While bigger firms (like Apple or Microsoft) have their own AR devices, Vuzix’s agility and specialized know-how (it consistently won innovation awards at CES) make it a compelling small-cap play on the broader spatial computing trend.

Kopin (NASDAQ: KOPN)

HQ: USA; Supplier of microdisplays and optics for AR/VR and defense.

Kopin is a behind-the-scenes enabler of spatial computing hardware. The company develops advanced microdisplays and optical modules – the tiny screens and lenses that make augmented and virtual reality headsets work. Kopin’s technology lets you overlay digital imagery onto the real world through devices like smart glasses or fighter pilot helmets. In fact, Kopin’s components are used in some of the most demanding settings; for example, it supplies high-resolution displays for the F-35 military fighter’s helmet, where reliability and clarity are critical. This pedigree in defense and industry has given Kopin a head start on the kind of robust, miniaturized displays needed for broader AR/VR adoption.

Recently, Kopin’s business momentum has been picking up as spatial computing moves from concept to reality. The firm saw a 71% jump in revenue in late 2024, driven largely by demand for its displays in defense and other specialized markets. It also secured multi-million dollar contracts, such as a $7.5 million deal to provide AR displays for pilot headgear. These wins suggest that not only is Kopin’s tech best-in-class, but larger players are willing to pay for it. With decades of R&D and a broad patent portfolio in microdisplay tech, Kopin is positioned as a potential key supplier, or even acquisition target, in an emerging spatial computing hardware supply chain.

Immersion (NASDAQ: IMMR)

HQ: USA; Haptics IP leader powering touch feedback in XR and gaming.

Immersion specializes in something fundamental to spatial computing that often goes overlooked: the sense of touch. Visuals and audio are key in AR and VR, but touch feedback (known as haptics) makes virtual experiences feel real. Think of feeling a slight vibration when you press a virtual button or the recoil in a VR game gun. Immersion has spent decades developing and patenting such haptic technology, and it licenses these innovations to device makers across the tech industry. If you’ve felt a vibration in a game controller or a smartphone’s haptic buzz, there’s a good chance Immersion’s IP is involved behind the scenes.

Immersion’s position is akin to owning the “touch layer” of spatial computing. For example, in late 2023, Meta settled a dispute and signed a license to use Immersion’s haptic tech in its XR hardware. This means as Meta’s VR headsets and AR devices evolve with more advanced touch feedback – such as gloves or controllers that let users feel virtual objects – Immersion will earn a cut. Beyond VR gaming, haptics are finding uses in automotive interfaces and mobile devices, expanding Immersion’s addressable market. As AR/VR adoption grows, so will demand for richer haptic experiences to match the visual realism. Immersion, with its large patent portfolio and licensing model, is positioned to benefit broadly from that trend without having to build hardware itself.

Enterprise & Industrial Spatial Computing

Enterprise & industrial spatial computing carries the tech from gaming labs to construction sites, factory floors, and rail yards. Picture mixed-reality hardhats overlaying blueprints on steel beams or digital twins predicting a pump failure before it happens. The market is early but budget-backed; every percent of uptime saves millions. For investors in spatial computing stocks, these solution vendors promise sticky multi-year contracts, deep domain moats, and a long runway of brownfield digitization ahead.

Trimble Inc. (NASDAQ: TRMB)

HQ: USA; Industrial tech firm blending GPS, AR, and digital twins.

Trimble is a technology company at the crossroads of the digital and physical world, especially in industries like construction, agriculture, and transportation. Historically known for GPS and surveying equipment, Trimble has transformed itself to provide software and services that integrate real-world sensor data with digital models. In practice, this means a construction engineer can wear a mixed-reality hardhat (Trimble partnered with Microsoft to embed HoloLens tech in a helmet) and see the BIM 3D model of a building overlaid onto the construction site, catching errors before they happen. Trimble’s “extended reality” solutions aim to bring the precision of digital design directly into the field, yielding fewer errors and improved safety.

The thesis for Trimble is about the long-term digitalization of large, physical industries. The company’s positioning is unique: it already has deep roots in how these industries operate (through its positioning systems, mapping, and project management software). Now it is layering spatial computing on top of that. Trimble’s tools allow field workers to visualize underground utilities via AR or enable remote experts to guide repairs by seeing what on-site crews see. As infrastructure and construction demand grows globally, companies are pushing for more efficiency and accuracy – exactly what Trimble’s tech delivers. The company has steadily shifted toward a subscription and software-driven model, which could expand margins over time.

PTC Inc. (NASDAQ: PTC)

HQ: USA; Enterprise software provider fusing CAD, IoT, and AR.

PTC is an enterprise software company that has successfully bridged into the augmented reality space for industry. Known historically for its CAD and PLM (product lifecycle management) software, PTC added an AR platform called Vuforia to its portfolio, aiming to bring interactive 3D into the realm of factories and service teams. In practice, PTC’s AR tech allows a worker to use a headset or tablet and see things like an overlay of a machine’s operating data, or a step-by-step holographic guide to repairing that machine. PTC has been recognized as a leader in the enterprise AR market, and for multiple years running its Vuforia platform has been ranked a top solution by industry analysts.

The company’s strategic edge is the combination of AR with its other offerings. PTC can tie together a digital thread: the CAD model of a product, the IoT data from that product in the field (via its ThingWorx platform), and an AR experience (via Vuforia) that delivers relevant information to an employee in context. This makes technologies like digital twins very tangible. An oil rig operator can wear an AR device and see gauges and maintenance history hovering next to a valve, drawn from the twin in real time. As more industrial firms embrace AR for training, maintenance, and sales, PTC stands to deepen its role as a mission-critical vendor providing the software backbone for those experiences.

Hexagon AB (OTC: HXGBY)

HQ: Sweden; Global leader in 3D mapping, simulation, and digital twins.

Hexagon AB has become a global force in what it calls “digital reality” solutions, or digital twins of the physical world. If spatial computing is about merging digital and physical, Hexagon provides many of the tools to do just that. Its Geosystems division (which includes Leica Geosystems) makes laser scanners, LiDAR sensors, and mapping software that can capture factories, cities, or infrastructure in rich 3D detail. On the software side, Hexagon offers platforms to visualize and analyze this spatial data for purposes ranging from construction and mining to public safety and automotive design. The company is even integrating its tech with NVIDIA’s Omniverse platform to easily turn laser scans into photorealistic 3D models in the cloud, accelerating the creation of immersive, usable digital twins.

Hexagon’s strategy is to be a pick-and-shovel provider of digital twin adoption. It already serves clients in dozens of industries with mission-critical measurement and design tools, and it has steadily added AI and cloud capabilities to make that data actionable. As industries like construction, manufacturing, and city planning rely more on simulation, autonomy, and AR/VR visualization, Hexagon stands to benefit. Its portfolio touches the entire lifecycle: capturing real-world data, building virtual models, and feeding those models back into field work via AR. With a large installed base and recurring revenue from software, Hexagon provides a stable yet forward-looking spatial computing stock.