Warfare is an accounting problem. If you trade a $2 million interceptor for a $20,000 Shahed drone enough times, you don’t lose the engagement—but you do bankrupt the treasury.

This is the economic asymmetry that’s ending the heavy armor doctrine. For forty years, Western military power was defined by “exquisite” platforms: main battle tanks, aircraft carriers, and manned fighters that were too expensive to lose.

That logic works when you have total air superiority. But it becomes financial suicide when you’re fighting swarms of disposable quadcopters that cost less than an iPhone. “Quality” cannot defeat “quantity” if the quantity also possesses precision guidance.

In a near-peer conflict, a heavy tank is not an apex predator; it’s a multi-million dollar liability.

Washington knows this. The buzzwords you see buried in appropriations bills, terms like “Replicator” or “Attritable Mass”, are effectively an admission that the current model is broken. The generals know they need to stop buying Ferraris and start buying millions of explosive Toyotas.

That’s the thesis for the military drone stocks on this watchlist—the rotation of capital from “few and heavy” to “cheap and disposable.”

Attritable Mass & Tactical UAS

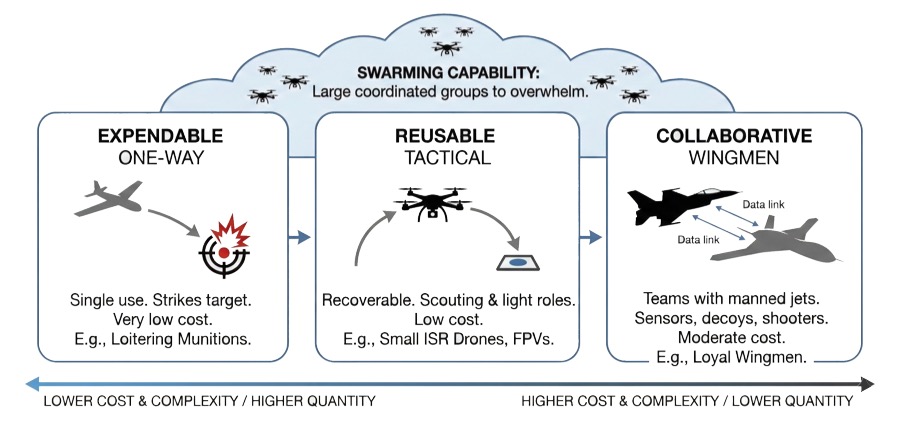

“Attritable” is Pentagon shorthand for “expendable.” It refers to platforms cheap enough to be shot down without causing a strategic or financial crisis. Unlike a $100 million F-35, which must return to base, an attritable drone can be traded for a target.

These military drone stocks cover two specific capabilities:

- Loitering Munitions (Kamikaze Drones): Systems that loiter, identify targets, and destroy them by impact. They act as precision mortars with infinite patience.

- Tactical ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance): Small, rucksack-portable airframes that give individual infantry squads “God’s eye” views of the battlefield.

The goal here is mass. The winner is not who builds the best drone, but who can manufacture 10,000 “good enough” drones that work in GPS-denied battlefields.

AeroVironment (NASDAQ: AVAV)

AeroVironment effectively created the loitering munition category with the Switchblade. While they manufacture larger surveillance drones (Puma), their valuation rests on the Switchblade 300 and 600 becoming standard infantry issue—the 21st-century equivalent of the hand grenade or mortar.

Ukraine demonstrated that a single soldier with a Switchblade 600 can destroy a T-90 tank. This asymmetric exchange ratio is the gold standard of modern procurement.

The 2026 Catalyst: Replicator Production Ramp. In 2024, the Pentagon selected the Switchblade 600 for the first tranche of its Replicator Initiative—a program designed to field thousands of autonomous systems to counter China’s mass. The catalyst is not just the delivery of these initial batches, but the subsequent integration of Switchblade into wider Allied procurement (specifically NATO and Taiwan). Watch for the transition from “emergency aid” contracts (Ukraine) to “program of record” stockpiling by the U.S. Army.

Kratos Defense (NASDAQ: KTOS)

Kratos operates in a different weight class. They do not make quadcopters; they make jet-powered drones that fly at high subsonic speeds. Their business was built on aerial target drones—jets designed to mimic cruise missiles for the Navy to shoot down. They have pivoted this technology into the “Loyal Wingman” concept: unmanned jets that fly alongside manned fighters to absorb fire or deliver munitions.

Their flagship, the XQ-58A Valkyrie, offers fighter-like performance for a fraction of the cost ($4 million vs. $80 million for an F-35), bridging the gap between disposable drones and exquisite fighters.

The 2026 Catalyst: Marine Corps CCA Program. While the Air Force has been slow to finalize its Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) plans, the US Marine Corps has moved quickly, effectively making the XQ-58A a program of record. Watch for the commencement of serial production for the Marines and the potential announcement of a “Tier 2” win with the Air Force. Success here looks like a confirmed order backlog exceeding 50+ airframes annually, validating the manufacturing line.

Red Cat (NASDAQ: RCAT)

Red Cat targets the “Blue UAS” opportunity—the federal mandate to purge Chinese-made drones (DJI) from U.S. government inventories. Their focus is strictly tactical: small, night-vision-capable drones for individual squads. Their acquisition of Teal Drones gave them the hardware, and their software ecosystem (swarming capabilities) provides the “moat.”

The thesis is simple: the U.S. Army needs a standard-issue Short Range Reconnaissance (SRR) drone to replace thousands of commercial Chinese units, and Red Cat is the domestic replacement.

The 2026 Catalyst: SRR Tranche 2 Deployment. Red Cat’s “Black Widow” system won the U.S. Army’s Short Range Reconnaissance (SRR) Tranche 2 contract. This is a key validation. Watch for the revenue realization from this win as full-rate production hits the balance sheet. Also, watch for the “NATO spillover” effect—European allies often adopt U.S. Army standards for interoperability. A significant export contract to a NATO member in 2026 would prove the platform’s scalability beyond the Pentagon.

Elbit Systems (NASDAQ: ESLT)

Elbit is the dominant defense electronics firm of Israel, a country that has been fighting a drone war for decades. Unlike U.S. pure-plays, Elbit is a diversified prime contractor, but their “attritable” portfolio is battle-hardened. They produce the SkyStriker (a direct competitor to the Switchblade) and the Lanius (a micro-drone designed for indoor trench/urban warfare).

The thesis here is “combat proven.” While many U.S. firms test on ranges, Elbit’s systems are currently being refined in high-intensity urban combat in Gaza and Southern Lebanon. They offer the most mature “sensor-to-shooter” cycle in the market.

The 2026 Catalyst: European Rearmament Orders. Europe is currently buying off-the-shelf solutions to refill depleted stocks. Elbit is a primary beneficiary because their production lines are hot, and their tech is proven. Watch for the expansion of SkyStriker sales into Eastern Europe (specifically Poland and Romania) and the integration of their “Legion-X” autonomous swarming software into NATO brigades. Elbit rides the conversion of geopolitical anxiety into a hard backlog.

AIRO Group (NASDAQ: AIRO)

AIRO Group is the “Transatlantic Bridge” for attritable warfare. If you believe the best R&D lab is a trench in the Donbas, AIRO is the purest play on that reality. AIRO’s strategy is to industrialize what’s already downing Russian tanks. Through its “Sky-Watch” division, they supply the RQ-35 Heidrun—a fixed-wing surveillance drone with proven GPS-denied performance—to NATO allies.

However, their core thesis lies in their late-2025 Joint Ventures with Ukrainian manufacturers “Nord-Drone” and “Bullet.” Instead of reinventing the wheel, AIRO is using its US capital and manufacturing infrastructure to scale the production of Ukrainian-designed FPV strike drones and jet-powered interceptors. They are effectively importing “combat-proven” IP to the US industrial base.

The 2026 Catalyst: “Nord-Drone” Production Ramp. In late 2025, AIRO announced plans to scale their Joint Venture production from 4,000 units per month to 25,000. Watch for the first major deliveries of US-manufactured Nord-Drone variants to NATO stockpiles. Success here proves they can convert “garage-built” lethality into an aerospace-grade program of record.

Counter-UAS Specialists

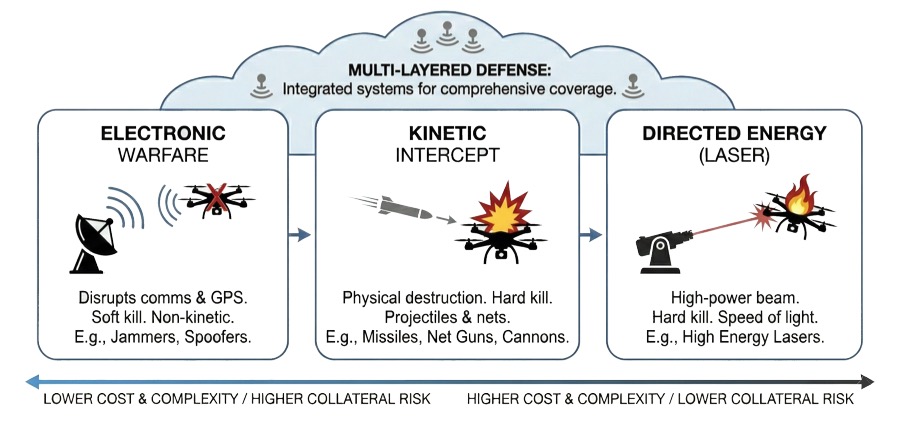

This segment addresses the inverse of the “accounting problem.” A defender will always run out of interceptors before an attacker runs out of drones.

The solution is “cost-per-shot” parity. This segment is defined by the race to the bottom in interception costs. It moves from expensive kinetic interceptors (missiles) to cheaper kinetics (bullets/proximity fuses) and finally to the holy grail: non-kinetic defeat (electronic warfare and lasers).

The thesis for these military drone stocks is defensive solvency. Clear the sky without bankrupting the user.

Leonardo DRS (NASDAQ: DRS)

Leonardo DRS is a lead incumbent for mobile force protection. DRS holds the key Program of Record for the U.S. Army’s Mobile-Low, Slow, Small Unmanned Aircraft Integrated Defeat System (M-LIDS). This is the current standard for protecting armored columns.

Their approach is pragmatic: integrate kinetic weapons (guns/missiles) with electronic warfare onto a single Stryker or vehicle chassis. It’s an integrated turret that detects, tracks, and jams or shoots. In October 2025, DRS solidified this lead by taking first place in the Pentagon’s JCO counter-drone competition with their “Ring” system, proving they can dominate the electronic warfare side of the equation as well as the kinetic.

The 2026 Catalyst: M-LIDS Production Ramp & “Ring” Integration. Watch for the industrial scaling of the M-LIDS program. The Army has moved from testing to fielding, and DRS is the prime integrator. Watch for the formal inclusion of the newly validated “Ring” electronic warfare capabilities into the standard M-LIDS configuration for 2026 block upgrades. This creates a “razor and blade” dynamic where DRS upgrades the very fleets it just built, compounding revenue per vehicle.

DroneShield (ASX: DRO, OTC: DRSHF)

DroneShield operates in the “soldier-portable” niche. Their DroneGun—a sci-fi-looking rifle that shoots radio waves to sever drone command links—has become the iconic image of counter-drone warfare in Ukraine. Unlike massive vehicle-mounted systems, DroneShield provides immediate personal protection for infantry.

Their thesis has evolved from hardware sales to software dominance. Their AI engine, DroneSentry-C2, constantly updates its library of drone signatures, allowing their hardware to recognize and jam new frequencies as enemy tactics shift. It’s effectively an “antivirus software” for physical airspace.

The 2026 Catalyst: SaaS Margin Pivot. Mid-2026 is scheduled for the rollout of their “RFAI-ATK” SaaS model. This is the critical valuation pivot. DroneShield is valued as a hardware manufacturer; the catalyst is the transition to recurring software revenue. Also, keep an eye on the realization of their $25 million Latin American contract and the activation of new US manufacturing capacity, which aims to quadruple potential throughput to over $2 billion annually.

Electro Optic Systems (ASX: EOS, OTC: EOPSF)

Electro Optic Systems solves the “hard kill” problem with extreme precision. Electronic jamming doesn’t work on autonomous drones that don’t need a signal to find their target. You have to shoot them down. The EOS “Slinger” system uses a 30mm cannon with a radar and wind sensor so precise it can snipe a moving quadcopter from a moving truck. It turns “dumb” bullets into precision interceptors.

The thesis was validated in Ukraine, where over 200 systems are currently active. They have further hedged their bet by securing the world’s first export contract for a 100kW High Energy Laser weapon to a NATO member, positioning them to own both the “bullet” and “beam” intercept markets.

The 2026 Catalyst: NATO Backlog Conversion. In late 2025, EOS secured orders from Western European NATO members specifically for the Slinger. Watch for the delivery and revenue recognition of this backlog, which now exceeds $400 million. Unlike speculative pilots, these are signed production orders. Watch for the performance data from these NATO deployments to trigger a wider adoption across the alliance, effectively making Slinger the standard “hard kill” solution for European ground vehicles.

Private Bellwethers & IPO Watch

These companies are currently private, but they’re a big reason legacy primes are sweating. They operate with Silicon Valley speed rather than Pentagon bureaucracy. While you cannot trade these tickers on the open market yet, their activities dictate the pricing power of the public incumbents. A 2026 IPO from any of them would be the sector’s defining financial event.

Anduril Industries (IPO Watch)

Anduril is the “SpaceX of Defense.” Beyond building weapons, they also build the software “Lattice” that connects them. Their thesis is vertical integration: own the sensor, the shooter, and the operating system. Anduril’s “Arsenal-1” factory in Ohio is a hyper-scale manufacturing plant designed to pump out autonomous weapons like cars. Their jet-powered “Fury” drone is the direct competitor to Kratos’ Valkyrie for the Air Force’s massive CCA contract.

The 2026 Catalyst: “Arsenal-1” Activation & CCA Decision. Production at the Arsenal-1 facility is scheduled to come online in H1 2026. This will be the first time a defense startup attempts automotive-scale production of military hardware. Simultaneously, the Air Force is expected to make definitive down-select decisions for the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program. If Anduril wins a major share of CCA while proving it can mass-produce at Arsenal-1, chances for a follow-up IPO filing would increase.

Shield AI (IPO Watch)

Shield AI solves the “GPS Denied” problem. Their “Hivemind” software allows drones to fly and fight in environments where GPS and communications are jammed—a scenario guaranteed in a near-peer war. Their flagship airframe, the V-BAT, is a unique VTOL (Vertical Take-off and Landing) drone that requires no runway, making it perfect for the dispersed, island-hopping strategy of the Marine Corps in the Pacific. In late 2025, they solidified their global supply chain by launching a $90M manufacturing hub in India with JSW Defence, insulating them from US labor shortages.

The 2026 Catalyst: “V-BAT Teams” Deployment. Shield AI has moved beyond single drones to “V-BAT Teams”—swarms of drones operating autonomously under a single human commander. Watch for the operational deployment of these teams by US Special Operations Command or the Navy, such as a specific contract announcement regarding “autonomous swarming” (not just hardware delivery). This validation of their software margin profile would be the trigger for their public listing.

Epirus (IPO Watch)

Epirus is the “anti-swarm.” The company builds “Leonidas”—a high-power microwave (HPM) system that can fry the electronics of an entire drone swarm instantly. Unlike lasers (which can only hit one target at a time) or missiles (which run out), Leonidas is a “force field” with a deep magazine—as long as it has power, it can shoot. They are the only company effectively productizing HPM technology for tactical use, recently securing a $43.5M contract for their “Generation II” systems.

The 2026 Catalyst: Operational Deployment to the Pacific. The Army has been testing Leonidas prototypes for years. Watch for the transition from “testing in the desert” to “deployment in the Pacific.” A formal announcement that Leonidas units are being stationed in Guam or Japan to protect assets would confirm the technology has graduated to strategic necessity.

The Mosaic Endgame

The future force structure will be a “mosaic” of thousands of cheap, dispersed, and autonomous nodes. Destroy one node, the network heals and continues. Destroy a thousand, the factory prints more.

This means the defining metric for this era is not “superiority,” but throughput. The winners will be the companies that can treat complex robotics like ammunition—make them by the million, without defects, at margins that make the math work.

This watchlist provides a tiered approach to military drone stocks. Attritable Strike (AeroVironment, Kratos, Red Cat, Elbit, AIRO) captures the offensive pivot to mass-produced, disposable airframes. Counter-UAS (Leonardo DRS, DroneShield, EOS) addresses the defensive solvency crisis. Finally, the Private Bellwethers (Anduril, Shield AI, Epirus) are crucial additions to an IPO watchlist.