For the last three years, the AI narrative has been dominated by what happens on a screen. Type in a prompt. The LLM then writes code, summarizes earnings calls, or generates an image.

We’ve effectively built the world’s busiest office worker.

But the vast majority of the global GDP doesn’t happen in a browser tab. It happens in factories, logistics hubs, and on city streets.

This is the shift from “Generative AI” to “Physical AI.”

For that to happen, computer vision is the enabling technology—specifically, the transition from simple image recognition to “spatial intelligence.”

By applying the same transformer models that power ChatGPT to visual data, machines are now learning to understand depth, physics, and cause-and-effect. A robot no longer sees a collection of pixels; it now understands those pixels as “a wooden pallet, partially obstructed, and safe to approach from the left.”

The Eyes of Embodied AI

Current AI applications face a value ceiling. You can’t prompt your way into unloading a truck or assembling a battery pack. The key thesis behind computer vision stocks: unlocking physical domains where AI can finally deliver ROI beyond knowledge work.

Industrial Machine Vision

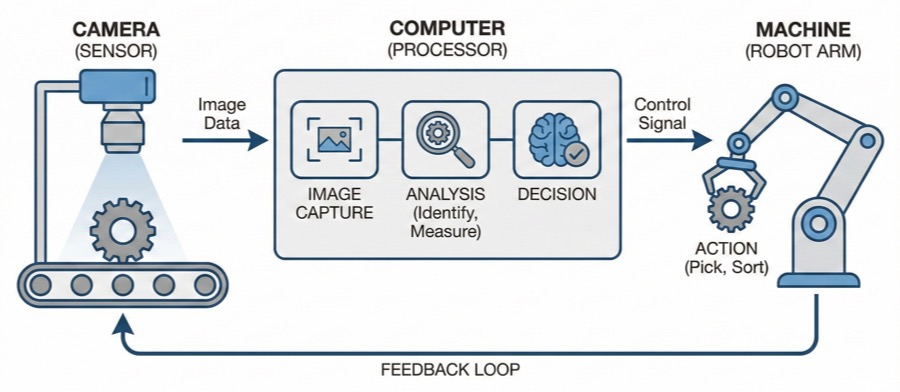

The “dumb” era of machine vision is over. For decades, this sector was defined by rigid, rule-based cameras performing binary tasks: Is the label there? Yes/No. Is the bottle cap twisted shut? Yes/No. It was useful, but brittle.

The current thesis for these computer vision stocks is the migration from inspection to guidance.

Think: “unstructured robotics.” Old robots needed parts presented in exact, millimeter-perfect jigs. New robots, equipped with AI-enabled vision, can look into a chaotic bin of mixed parts, identify the correct one, determine its orientation, and grasp it.

This capability breaks the rigid constraints of the assembly line, allowing automation to enter unstructured environments like warehouses and loading docks.

Cognex Corporation (NASDAQ: CGNX)

Cognex is the bellwether, but the narrative here is shifting from “logistics volume” to “edge intelligence.” The historical knock on machine vision was the complexity of setup—you needed a specialized engineer to program the rules. Cognex’s new thesis rests on “Edge Learning” (specifically their ViDi EL platform).

They are embedding the AI training directly into the camera. You don’t need a server farm or a data scientist; a line operator presents five “good” parts and five “bad” parts to the camera, and the device trains itself in minutes. This lowers the deployment cost of vision by an order of magnitude, opening up millions of inspection points that were previously too expensive to automate.

Watch their In-Sight L38 3D systems—this is the hardware layer that gives robots depth perception, a prerequisite for the physical manipulation of objects.

Basler AG (XETRA: BSL, OTC: BSLG)

If Cognex is the premium, high-margin player, Basler is the “volume enablement” play. Their thesis is the commoditization of sight. Basler specializes in embedded vision—stripping the camera down to a bare sensor and board that can be integrated directly into a medical device, a roving logistics robot, or a smart agriculture drone.

The value proposition here isn’t really the hardware; it’s the ecosystem. Basler has aggressively integrated with the Siemens Industrial Edge and the ROS (Robot Operating System) communities. They are effectively becoming the “eye” standard for the mid-range robotics market. As mobile robots move from pilot projects to fleet deployments, Basler’s unit volumes provide the leverage.

Teledyne (NYSE: TDY)

Teledyne is the conglomerate of “superhuman” senses. While Cognex and Basler focus largely on the visible spectrum, Teledyne’s thesis is built on multispectral imaging. Their portfolio—bolstered by the FLIR acquisition—covers thermal, X-ray, and Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR).

This matters because next-gen computer vision needs to understand properties that pixels alone cannot convey. A robot handling chemical drums needs thermal vision to detect leaks; a food sorting bot needs SWIR to see bruising under the skin of an apple.

Teledyne provides the sensory cortex for high-stakes industrial environments where visible light is insufficient. Their Bumblebee X stereo camera series is the direct play here, providing the dense depth maps required for autonomous mobile robots to navigate complex, changing environments.

Spatial Intelligence

If machine vision is the “eye,” spatial intelligence is the “cortex.” This segment of computer vision stocks captures the transition from 2D pixel processing to 3D volumetric understanding. In this domain, software cannot stop at just seeing the object; value comes from calculating its precise geospacial coordinates, its physical dimensions, and its relationship to other objects in real-time.

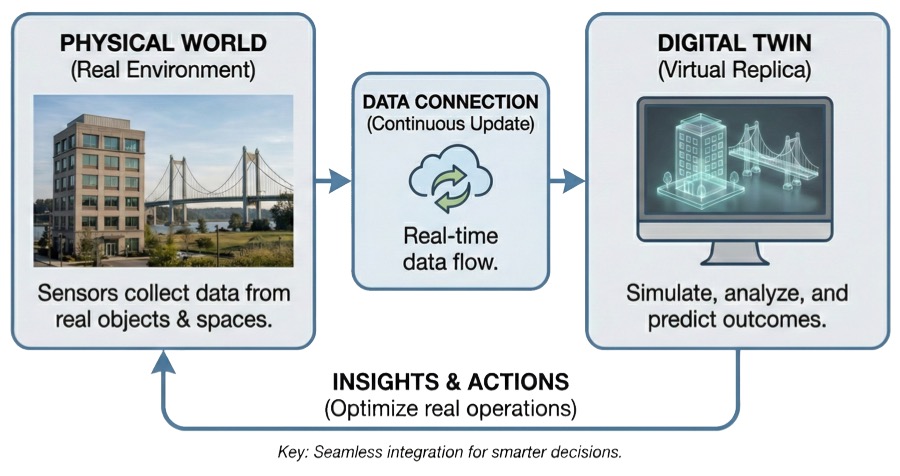

This is the foundation of the “Industrial Metaverse”—not as a VR playground, but as a rigorous, millimeter-accurate digital twin of the physical world that allows operators to simulate changes before pouring concrete or moving machinery.

Bentley Systems (NASDAQ: BSY)

Bentley is often miscategorized as a legacy CAD provider, but its new thesis revolves around the “iTwin” platform. The value proposition here is the resolution of the data-loss problem in construction. Historically, engineering data died the moment a building was finished; the digital models were discarded, and operations teams relied on paper schematics. Bentley’s iTwin captures the “living” asset.

By integrating photogrammetry and sensor data, they create a dynamic digital replica of bridges, grids, and rail networks that updates in real-time. This allows for predictive maintenance based on actual physics engines rather than simple schedules. The growth vector here is not the design software, but the recurring revenue derived from managing the data lifecycle of the world’s largest infrastructure projects.

Trimble Inc. (NASDAQ: TRMB)

Trimble is the execution layer of spatial intelligence. While Bentley models the world, Trimble provides the hardware and software that allows machines to manipulate it. The thesis here is “connected autonomy.” Trimble creates the digital feedback loops that allow an excavator to dig a trench to within a centimeter of a blueprint without human guidance, or a tractor to plant seeds with sub-inch precision.

They have effectively cornered the market on “ground truth.” As labor shortages force the construction and agriculture sectors to adopt semi-autonomous machinery, Trimble’s precise positioning technology becomes the non-negotiable operating system for the physical worksite.

Ouster (NASDAQ: OUST)

Ouster represents the perception layer for smart infrastructure. The company has successfully pivoted from a pure-play autonomous vehicle bet to a broader “digital lidar” thesis. Unlike legacy analog lidar, Ouster’s digital architecture follows Moore’s Law, allowing for rapid performance gains and cost reduction.

The key narrative driver is their Gemini perception platform. This software layer ingests raw lidar data and outputs actionable crowd analytics, traffic management insights, and security alerts.

The bear case for Ouster is that AV adoption stalls; the bull case is that Ouster installs thousands of sensors on traffic lights, toll booths, and factory ceilings, becoming the privacy-preserving alternative to camera surveillance for tracking the movement of people and assets in 3D space.

Edge Vision Processors

The cloud is too slow for the physical world. If a robot drops a pallet or a car detects a pedestrian, it cannot wait 200 milliseconds for a data center in Virginia to process the video feed and send back a command. Physics happens in real-time; intelligence must do the same.

The thesis for this segment of computer vision stocks is inference at the edge. We are moving compute power out of the server farm and directly into the device itself—highly specialized, low-power silicon designed to run neural networks on a battery budget.

This solves three non-negotiable problems in physical AI: latency (speed of light is a hard cap), bandwidth (uploading terabytes of raw video is expensive), and privacy (data stays on the device).

Ambarella (NASDAQ: AMBA)

Ambarella has successfully executed a difficult pivot from consumer video (GoPro chips) to AI domain controllers. Their thesis relies on the CVflow architecture, a proprietary design that processes neural networks differently than a standard GPU. While NVIDIA dominates the training of AI models in the cloud, Ambarella aims to compete for the inference of those models on the device.

Their CV3 family of SoCs is the flagship here. It allows an autonomous vehicle or delivery robot to process inputs from up to 20 sensors (cameras, radar, and lidar) simultaneously on a single chip, consuming a fraction of the power of a trunk full of computers. It’s betting on their “efficiency-per-watt” advantage becoming the industry standard as AI models get heavier and battery life remains a bottleneck.

Lattice Semiconductor (NASDAQ: LSCC)

Lattice plays a different game. They do not make rigid System-on-Chips (SoCs) like Ambarella; they make FPGAs (Field Programmable Gate Arrays). These are chips that can be rewired via software after they leave the factory.

In the messy world of industrial vision, standards change constantly. A warehouse robot might need to interface with a Sony sensor today and a Teledyne sensor tomorrow. Lattice chips act as the flexible “glue” logic that bridges these incompatible signals with near-zero latency.

Their Avant and CrossLink platforms are specifically designed for “sensor fusion”—merging data from thermal, infrared, and optical sensors before it even reaches the main processor. The thesis here is adaptability: as vision standards evolve, Lattice hardware survives because it can be reprogrammed in the field.

CEVA, Inc. (NASDAQ: CEVA)

CEVA is the IP play of the sector. They generally do not manufacture chips themselves; they license the intellectual property that allows other chipmakers to add smart sensing to their silicon. Their thesis is the proliferation of “tiny vision” into disposable or ultra-low-cost devices—smart doorbells, hearing aids, and wearables—where a $50 Ambarella chip is too expensive and power-hungry.

CEVA’s NeuPro-M NPU (Neural Processing Unit) IP allows a generic microcontroller to run complex vision transformers. The economic moat here is the high switching cost of IP; once an engineer builds their vision stack on CEVA’s digital signal processors, they rarely switch. CEVA is a play on the long tail of the IoT market, rather than the high-performance robotics core.

Bridging the Reality Gap

LLMs have already read the entire public internet. The marginal return on scraping web text is approaching zero. The next leap in model performance will require data that cannot be scraped: the torque of a specific bolt, the thermal signature of a failing turbine, or the precise depth of a pothole.

This creates a “Reality Gap.”

This watchlist provides a tiered approach to bridging that gap. Industrial Machine Vision (Cognex, Basler, Teledyne) secures the execution layer, allowing robots to identify and grip objects in chaotic environments. Spatial Intelligence (Bentley, Trimble, Ouster) establishes the context, building the millimeter-accurate digital twins that autonomous systems must navigate. Finally, Edge Vision Processors (Ambarella, Lattice, CEVA) solve the hardware constraints, moving compute power directly to the sensor to bypass the latency of the cloud