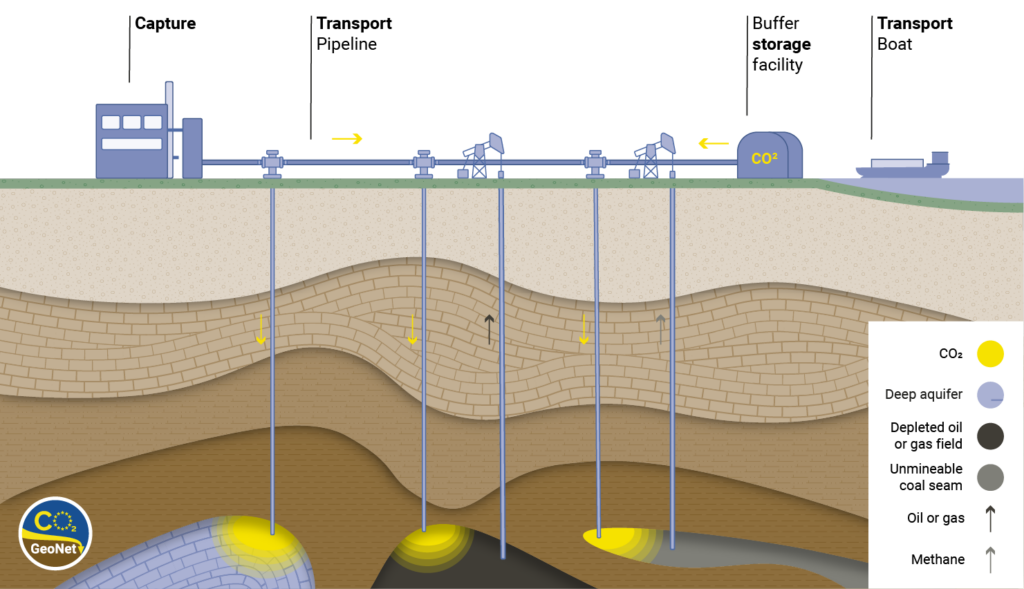

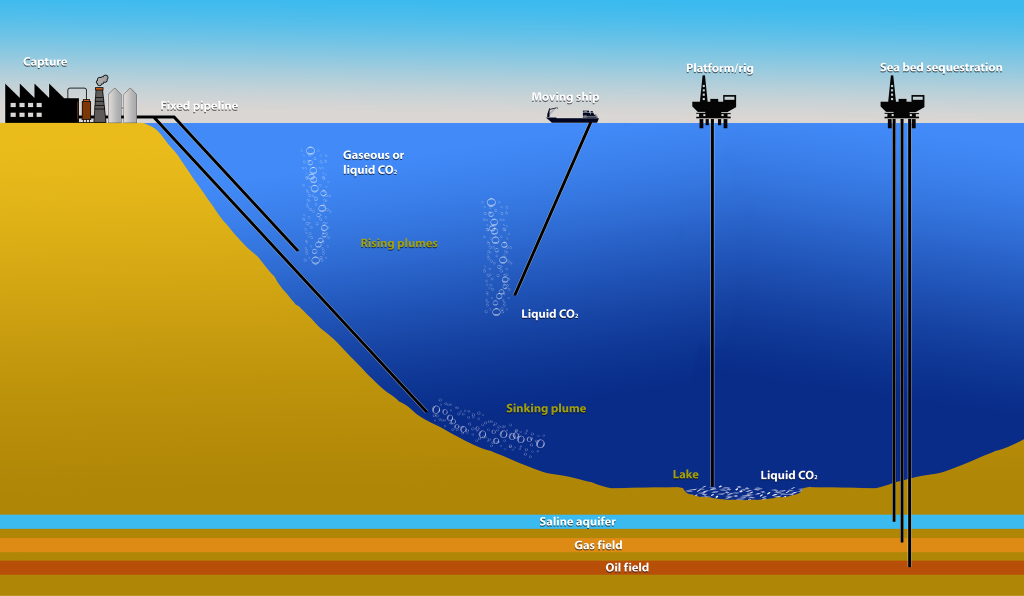

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) aims to trap carbon dioxide from factories and power plants—or even pull it from the air directly. That carbon is then stored deep underground or in the ocean, or reused in products. The pitch for CCS is simple: let hard-to-electrify heavy industries keep making steel, cement, and fuels while cutting emissions. For years, the promise ran ahead of reality. Projects were expensive one-offs, and the supporting pieces—pipelines, storage sites, long-term contracts—were thin on the ground. That’s starting to change as policy evolves and companies start signing real offtakes. The installed base is still tiny next to the problem, which leaves a wide runway.

In this report, we outline how to invest in carbon capture stocks and what to watch in the buildout—so exposure can stay durable even as technologies and incentives evolve.

Why Carbon Capture, Why Now?

- First, the policy floor got real. In the U.S., the 45Q credit now meaningfully covers the hardest costs (up to $85/ton for point-source storage and $180/ton for direct-air capture into storage, with transferability/direct pay intact). In Europe, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism exits its reporting trial and switches on actual payments in 2026, which pushes heavy industry to cut embedded emissions or pay at the border. Together, that’s a clearer revenue path for capture, transport, and storage.

- Second, the full chain is finally operating at scale. In June 2025, Heidelberg Materials opened the Brevik CCS facility (designed to capture ~400,000 t/yr from cement). In August 2025, its CO₂ was shipped and injected into Norway’s Northern Lights storage site—Europe’s first cross-border, open-access CO₂ storage service. In the U.S., more states now hold Class VI “primacy” to permit CO₂ storage wells themselves (North Dakota, Wyoming, Louisiana, West Virginia), with Texas on track pending a final EPA rule. The result is fewer bottlenecks and a clearer path from project to operation. Meanwhile, the global CCS pipeline is set to roughly double capture capacity once under-construction plants come online.

Reality check: it’s still early and uneven. EU carbon prices sit well below prior peaks, and permitting timelines remain measured. EPA’s own guidance targets ~24 months for complete Class VI reviews, so lead times are real. But with the policy floor in place, the first commercial chain injecting, and permitting authority expanding, the investable pieces now look more like assets than experiments.

How to Invest in Carbon Capture

The challenge with carbon capture stocks today is that the investable pieces are scattered. Many dedicated developers are still private, and the public names that touch capture often house it inside larger industrial or energy portfolios. Pure-play exposure exists, but it’s early and capacity is only beginning to scale.

In this report, we look at the theme through a few practical angles: direct exposure to capture projects, diversified operators that control or finance the pipes and storage, and the picks-and-shovels enablers. We’ll also track notable private companies in case listings or acquisitions open cleaner ways to own the trend.

Carbon Capture & Storage Platforms

Pure-play carbon capture stocks are still rare, but the category is stepping into the mainstream. This sleeve looks at three direct ways to own the buildout: a next-generation power producer with capture by design, an industrial provider turning bespoke projects into repeatable packages, and a listed platform assembling an integrated CCS portfolio. Together they offer early, focused exposure to capture and storage.

NET Power Inc. (NYSE: NPWR)

HQ: USA; Allam-cycle gas power with built-in CO₂ capture.

NET Power offers exposure to a technology that aims to deliver “always-on” clean power with CO₂ captured by design. Its Allam-Fetvedt Cycle rethinks gas generation by burning natural gas with oxygen and using supercritical CO₂ as the working fluid, so capture is built in rather than bolted on. That makes the output pipeline-ready CO₂ plus grid-reliable electricity—exactly what utilities want as they add renewables but still need 24/7 capacity.

The near-term plan is pragmatic: deploy “Project Permian” in Texas with a stepwise, integrated configuration that adds conventional gas turbines first and then ties them into the NET Power cycle. Management says that unlocks earlier megawatts and a levelized cost of energy targeted below $100/MWh, a line in the sand that can win real offtakes. Meanwhile, its La Porte test facility continues to rack up operating hours to validate components and de-risk commercialization.

Execution is anchored by blue-chip partners. Baker Hughes is co-developing the specialized sCO₂ turboexpander and related turbomachinery, with long-lead orders already moving—a crucial supply chain advantage for first-wave plants. The flagship Odessa/Permian site ties directly into mature CO₂ handling in the basin, and the company is also pursuing a California program with Carbon TerraVault targeting up to 1 GW of low-carbon baseload.

Capsol Technologies ASA (OSE: CAPSL)

HQ: Norway; Heat-integrated carbonate solvent capture for heavy industry.

Capsol is a picks-and-shovels play on industrial carbon capture. Its heat-integrated, hot-potassium-carbonate process is familiar to regulators and operators. The idea is to use a solvent that’s proven, safer to handle than amines, and paired with smart heat recovery so plants can capture 95%+ of CO₂ with attractive operating economics. That’s resonating in the heaviest emitters—cement, waste-to-energy, biomass—and now gas turbines via CapsolGT, which captures directly off the exhaust.

Commercial momentum is visible. Capsol’s mature pipeline reached ~22.6 Mtpa of capture capacity and H1-2025 revenues climbed, reflecting multiple projects marching into higher-value phases. The marquee reference: Stockholm Exergi’s final investment decision for what it calls the world’s first large-scale BECCS plant, scheduled to remove ~800,000 t/yr and using CapsolEoP. That anchor helps standardize specs and bankability across the segment.

Capsol also leverages a capital-light model—licensing plus services—scaled by “CapsolGo” demo campaigns that shorten sales cycles, and it has added financing flexibility (e.g., a green loan backed by InvestEU) to support growth. Put together, Capsol offers clean exposure to the build-out of industrial capture: technology that plants can permit, a widening set of end-markets, and a pipeline that’s maturing from studies into FEED and construction.

CO2 Energy Transition Corp. (NASDAQ: NOEMU)

HQ: USA; CCUS-focused SPAC pursuing midstream, storage, and technology.

CO2 Energy Transition is a SPAC built to bring carbon-capture value chains into the public markets. It raised roughly $69 million in November 2024, listing units as NOEMU (with the common shares, warrants, and rights trading separately thereafter). The mandate is explicit: pursue a business combination in carbon capture, utilization, and storage—exactly where private developers and midstream/storage platforms are scaling but still capital-hungry.

The thesis here is optionality. As a blank-check company, CO2 Energy Transition can target capture technology providers, CO₂ midstream (compression, pipelines, shipping), or storage developers, and assemble a platform that benefits from policy support like U.S. 45Q and Europe’s cross-border build-out. Its materials outline a strategy spanning lower-carbon power, fuels, and CCUS services, with a team rooted in energy operations and CO₂ projects. Headquarters in Houston places it near key project pipelines and sequestration hubs.

For investors, that means a way to convert today’s private-market pipeline into a public pure-play as the sector consolidates. If the team secures an attractive target, you get a listed vehicle with immediate scale in CCUS; if the opportunity set shifts, the SPAC format preserves flexibility to pivot within the ecosystem.

See the Private Companies to Watch section for notable names to keep an eye on.

Diversified CCS Operators & Integrators

Diversified operators and integrators can earn across the value chain. These companies pair deep industrial know-how with capital discipline, long-term contracts, and policy support. Among carbon capture stocks, this sleeve offers broad, durable exposure across capture, transport, and storage—and can translate the buildout into infrastructure-style cash flows.

Occidental Petroleum (NYSE: OXY)

HQ: USA; Oil major building DAC and CO₂ storage.

Occidental is a U.S. oil & chemicals company that has built a second franchise around carbon management. It owns 1PointFive, the platform developing direct-air capture (DAC) and storage hubs, and it now fully controls key DAC IP after closing the acquisition of Carbon Engineering in early 2024. The Carbon Engineering acquisition tightens the feedback loop between technology, EPC, and operations—useful for lowering costs each generation—and optional international JVs open new markets without over-stretching the balance sheet.

1PointFive’s flagship is STRATOS in Ector County, Texas—designed to pull up to 500,000 tons of CO₂ a year straight from ambient air and targeted to begin commercial operations in 2025, with Class VI storage permits in hand. The company has also built a credible book of long-dated carbon removal offtakes with blue-chip buyers like Microsoft, Amazon, and Airbus, anchoring demand for early plants.

Oxy’s century of subsurface and CO₂-handling expertise gives it an edge as capture scales from pilots to standardized plants connected to licensed storage. With STRATOS setting a utility-style template and a pipeline of corporate buyers already paying for removals, Oxy can compound returns as more modules, more hubs, and more storage wells come online under supportive U.S. policy (45Q) and growing corporate decarbonization budgets.

SLB (NYSE: SLB)

HQ: USA; Energy-tech leader for capture and storage projects.

SLB is an energy-technology leader whose core strengths—geology, well engineering, and project delivery—map directly onto carbon capture and storage. In 2024, it closed a joint venture with Aker Carbon Capture (now branded SLB Capturi), combining capture technology with SLB’s global reach. The JV’s first modular plant entered operation in the Netherlands in January 2025, while the team continues to win European FEED and delivery mandates. On the storage side, SLB rolled out its Sequestri digital toolkit in 2025 to help developers screen, model, and de-risk reservoirs—again leaning into SLB’s software and subsurface DNA.

Strategically, SLB is building a full-stack CCS offering—from capture units to the subsurface systems that make storage bankable. This gives it multiple ways to participate as cement, waste-to-energy, power, and blue-hydrogen projects move from studies to FIDs. The company can monetize near-term equipment and services (modular capture), mid-cycle software and engineering (Sequestri, storage evaluation), and long-cycle project delivery.

Large anchor projects, such as the planned 9-million-ton-per-year CCS hub in Jubail with Aramco and Linde, further validate SLB’s role at giga-scale and open pull-through across its portfolio. As more regions adopt incentive frameworks, SLB’s standardized capture blocks plus its storage toolchain should shorten timelines and broaden margins, making it one of the cleanest diversified ways to own the CCS buildout.

Linde (NASDAQ: LIN)

HQ: Ireland; Industrial gases giant scaling capture-enabled clean molecules.

Linde is the world’s largest industrial-gases company and a seasoned process-plant engineer. That combination matters in CCS because capture is a chemistry and scale game. In the U.S., Linde is building a new hydrogen facility in Texas to supply OCI/Woodside’s world-scale blue ammonia plant—and has signed ExxonMobil to transport and permanently store up to 2.2 million tons of CO₂ per year from Linde’s operations starting in 2025. Beyond the Gulf Coast, Linde agreed to invest over $2 billion in a clean-hydrogen plant for Dow’s Path2Zero complex in Alberta, with plans to capture and sequester over 2 million tons annually.

Linde also brings an in-house capture toolkit (advanced amines with BASF and adsorption-based systems) that it can bolt onto its hydrogen and industrial-gas footprints or deliver to third parties. And at giga-scale, Linde is a 20% partner (alongside SLB) in Aramco’s planned 9 Mt/yr CCS hub at Jubail, slated for late-decade start-up.

In essence, Linde monetizes CCS in three reinforcing ways—selling “clean molecules” (hydrogen with embedded capture), selling capture plants and solvents, and taking equity in large CO₂ networks where that unlocks long-term gas sales. With multi-million-ton offtakes already contracted and a backlog tied to ammonia, chemicals, and plastics decarbonization, Linde offers durable, infrastructure-like exposure to capture and storage while keeping the upside from its global engineering pipeline.

Air Products & Chemicals (NYSE: APD)

HQ: USA; Hydrogen powerhouse integrating capture into molecule sales.

Air Products is a global hydrogen leader turning that scale into carbon-capture cash flows. It has real operating history—since 2013 the company has captured roughly 1 million tons of CO₂ per year from its Port Arthur hydrogen plants and sent the gas for permanent storage via Gulf Coast infrastructure. The next step up is the $4.5 billion Louisiana Clean Energy Complex: a blue-hydrogen hub designed to capture and sequester over 5 million tons of CO₂ annually at ~95% capture, now working through state Class VI technical reviews.

In Canada, Air Products is building a net-zero hydrogen energy complex in Edmonton that captures more than 95% of process CO₂ and uses hydrogen-fueled power to offset the rest—an integrated blueprint for decarbonized molecules in a major industrial basin.

APD’s strategy is to own and operate the full hydrogen-with-CCS value chain—feedstock reforming, capture, pipeline, and storage tie-ins—then sell long-term molecules to refineries, ammonia plants, and heavy industry. With operating CCS credentials on the Gulf Coast, a multi-million-ton Louisiana project advancing, and a Canadian complex that demonstrates near-zero-carbon hydrogen at scale, APD sits at the center of where policy, customers, and geology line up. That positions the company to compound through take-or-pay contracts and repeatable project templates as hydrogen and ammonia decarbonize supply chains.

Private Companies to Watch

Many carbon capture leaders remain private, but their progress is a bellwether for public carbon capture stocks. The standouts are moving from pilots to commercial operation, signing multi-year offtakes, and attracting substantial strategic capital. Approaches range from direct-air capture systems to CO₂-to-jet-fuel via power-to-liquids, each addressing a different chokepoint in the chain.

Climeworks (Private)

HQ: Switzerland; Direct air capture pure-play and carbon removal seller.

Climeworks is the most established pure-play in direct air capture (DAC). Founded in Switzerland, it runs commercial plants in Iceland, including Mammoth—designed for up to 36,000 tons per year—and sells long-dated carbon-removal contracts to blue-chip buyers. In the U.S., it’s an anchor technology provider in the DOE-backed “Project Cypress” DAC hub in Louisiana alongside Battelle and Heirloom, unlocking federal cost-share and a pathway to megaton-scale deployments under the 45Q framework. Climeworks has continued to raise growth capital, including a $162 million round in July 2025, and has landed multi-year removals like a 40,000-ton deal with Morgan Stanley.

Climeworks offers the cleanest line of sight to scaled DAC revenues: proven plants, rigorous MRV, and corporate offtakes that lengthen cash-flow duration. Its participation in federally supported hubs de-risks infrastructure and creates options around low-cost, permanent storage—critical to reaching $/ton targets at scale. As Europe’s CO₂ transport and storage opens up—Northern Lights is now operating—Climeworks can position projects wherever the storage is bankable, not just where emitters sit. Climeworks remains the category’s pacing brand with a growing backlog and improving access to both policy and private financing.

Twelve (Private)

HQ: USA; CO₂-to-fuels electrolysis company making synthetic jet fuel.

Twelve is a Bay Area “carbon transformation” company turning CO₂, water, and renewable power into drop-in fuels and chemicals. Its flagship is E-Jet®, a power-to-liquids sustainable aviation fuel that meets ASTM D7566 specs. The first commercial facility—AirPlant™ One in Moses Lake, Washington—leverages abundant hydropower; United Airlines invested in 2025 as the plant moves toward initial output (targeting ~50,000 gallons/year to start). Twelve has also expanded funding this year to support buildout. Partnerships span airlines and tech firms (Alaska Airlines and Microsoft among early collaborators), anchoring real demand signals for e-fuels.

Twelve is a levered bet on power-to-liquids as aviation decarbonizes. It offers a clear offtake story—drop-in SAF that uses existing aircraft and fuel logistics—plus a modular electrochemical core (“Opus”) that can scale with cheap clean electricity and green hydrogen. In a landscape where most SAF pathways struggle to reach volume or fit infrastructure, Twelve’s route aligns with airline mandates and corporate Scope 3 goals while tapping policy tailwinds for e-fuels. Early commercial partnerships and on-the-ground capacity in Washington make it one of the few private ways to get direct exposure to synthetic SAF demand growth rather than broad energy exposure.

Svante (Private)

HQ: Canada; Modular solid-sorbent filters for point-source capture.

Canada’s Svante builds solid-sorbent “filters” and rotary contactor machines to capture CO₂ from industrial flue gas—cement, steel, hydrogen, refining. Its MOF-based structured adsorbents enable fast, steam-driven capture and release, designed for modular, continuous operation. In May 2025, Svante opened “Redwood,” billed as the world’s first carbon-filter gigafactory, capable of producing enough filters to capture up to 10 million tons of CO₂ per year. The company has strategic partnerships and supply lines with BASF (MOF materials) and energy/industrial players like Chevron and Samsung E&A, positioning it for rapid standardization and deployment.

Svante is the archetypal picks-and-shovels play for point-source capture. By productizing capture into compact filters and skid-mounted systems, it shortens project timelines and shifts value to manufacturing scale rather than one-off engineering. Redwood gives Svante a tangible capacity moat just as storage access expands and incentives (e.g., 45Q) favor capture on cement, hydrogen, and refinery stacks. With tier-one materials and EPC partners, Svante can replicate plants, drive learning-curve cost downs, and plug into emerging CO₂ transport and storage networks—turning industrial decarbonization into a repeatable equipment business rather than bespoke projects.